Malcolm Daniel

Curator Malcolm Daniel has been a leading light in the world of photography for close to four decades. He spent 23 years at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, before continuing his career at the Museum of Fine Ats, Houston, in 2013. He retired earlier this year, though he will continue as curator emeritus. Curator Lisa Volpe is the newly appointed head of the photography department at the museum. She joined the Museum in 2017 after stints in Cleveland, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara (where she earned her Ph.D. at UCSB), and Wichita.

The initial plan was to conduct a three-way discussion over the telephone. I sent off questions and topics beforehand. In the end, following delays and time restrictions, they carried out the discussion between themselves. I'm very grateful to them both.

Lisa Volpe

LV (Lisa Volpe): Malcolm, as I step into your shoes leading the MFAH Photography Department, I'm curious about your experience of moving from the Met to Houston back in 2013 to step into the shoes of Anne Wilkes Tucker. I think you overlapped with Anne for 18 months, and I wonder what that period was like.

MD (Malcolm Daniel): Yeah, when I moved here, I heard the phrase "big shoes to fill" over and over! I knew by reputation that Anne had built a great collection, but I didn't know Anne well, didn't know the collection in any detail, didn't know Houston, and didn't know the photography community here, so that period of overlap was really important because it gave me a chance to get up to speed before Anne stepped away. It was generous on Anne's part to step back after having founded and built the department and to still be there to guide and advise me as I took over. And I think it was important for our supporters to know that I had the "Anne Tucker Seal of Approval" rather than just coming in as the "new guy."

Still, I'm envious of your situation. In taking the reins now, you have the great advantage of already having developed a deep knowledge of the MFAH collection and a strong relationship with colleagues both in and out of the museum, and you're already beloved by our supporters. I think it's rare in our field for a new department head to begin with that important head start, and it's a testament to all your good work at the MFAH that director Gary Tinterow appointed you without any kind of a broader search. We've both seen a number of sister institutions where the obvious internal candidate was passed over for someone from the outside who lacked that knowledge of the collection and community. It's safe to say that you and I are both relieved that Gary was wise enough to know you were the ideal choice.

LV: Well, thank you! But it is a legacy situation! First Anne, and then you! I have TWO sets of "big shoes to fill"! It's been my absolute joy to be an MFAH employee for the past eight years, and it's a privilege to lead the department, one I acknowledge every day. The support from colleagues and donors has really bolstered me as I step into this position.

MD: Lisa, before joining the MFAH in 2017 as Associate Curator of Photography, you had fellowships at the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and you were then curator at Wichita Art Museum. Talk a little bit about your background, how you came to focus on photography, who your mentors were, what you learned in those positions, and what aspects of the medium's history are most exciting for you.

LV: Well, I've been in love with photography for as long as I can remember. My grandfather was a very serious amateur photographer and my mother said she used to wake up in the morning and find prints floating in her bathtub. So, when I set my sights on graduate school, I was thrilled to be offered a fellowship at Case Western Reserve and the Cleveland Museum of Art. It allowed me to earn my Masters while working for Tom Hinson at the museum. It was a great experience. Then I headed to California for my PhD and was lucky enough to be hired by the amazing Karen Sinsheimer at Santa Barbara, so I was working part-time while going to school again. Then I got a fellowship at LACMA for a bit, before going back to Santa Barbara. I really wanted to find a photo curator position, but there was nothing open! The positions are like gems, they're so rare and coveted! So, I applied for a curatorial position at the Wichita Art Museum as an American art curator, covering all time periods. And while I was there, I did my best to start a photography collection. That was exciting and complicated in the 2010s. Then, the position was posted for Houston...

MD: After your experience at those other museums, what drew you to the position in Houston, and what have you found surprising in your years at the MFAH?

LV: I've known about the world-renowned collection in Houston since my high school darkroom days. The exhibition catalogs that Anne produced were my own personal courses in photo history. And once I came to Houston, I learned that the collection was even richer than I had known! And that success can absolutely be attributed to the amazing donor base here in town. Honestly, I've been in a lot of cities and at a lot of museums, and no other museum has this kind of dedicated, involved, interested community of donors and supporters. It doesn't feel like "development" in the typical museum sense, it truly feels like family. And I couldn't be happier to be a part of it.

Let me turn the question around and ask you to look back and say what's been different or surprising about the MFAH for you after your years at the Met.

MD: Wow. I think one of the most surprising things–not just for our department, but for this Museum as a whole–is how much we do with a quite small staff. Even though the Photography Department is larger than most other curatorial areas at the MFAH, it's small compared to the department at the Met. There, each of the curators had his or her area of expertise and responsibility, and I think everyone was a bit territorial. So, for instance, my exhibitions at the Met all focused on nineteenth- or early twentieth-century photography, but here in Houston I've really enjoyed organizing small exhibitions of work by contemporary photographers–Vera Lutter, Fazal Sheikh, David Levinthal–and being the Houston point person for major exhibitions of Sally Mann, Dawoud Bey, and Thomas Demand, as well as co-curating our recent exhibition of contemporary Cuban photography. With just you and me as photography curators, I've been able to spread my wings a bit. I'll also say, related to that, that I'm grateful for the exceptionally collaborative and collegial relationship that you and I have enjoyed. That's not always the case in museums.

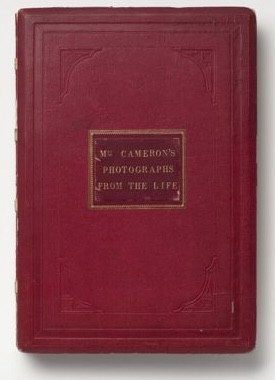

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs from the Life, 1864–69, album of albumen silver prints from glass negatives, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase.

LV: I was thinking that we should ask each other to name the three or four acquisitions we're most proud of, but it might be fun to play a game instead and have each of us guess how the other would answer. I know that the Norman Album of photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron and the very early whole-plate daguerreotype by Alphonse-Eugène Hubert would be on your list; and I'll guess that Laurie Simmons's Magnum Opus II (the Bye-Bye) might be on your list also. Tell us about those and let me know what I missed.

MD: Haha. Yeah. No big secret that the Norman Album and the Hubert would be on my list. For more than 30 years, I've known about the unique album of 75 photographs that Julia Margaret Cameron put together for her daughter and son-in-law Julia and Charles Norman as a thank-you for the gift of her first camera. Its purchase by the museum from the Norman descendants, through Hans Kraus, is the most important single object that I was able to acquire in my entire career. It's filled with exquisite prints of many of Cameron's most iconic images.

Early whole-plate daguerreotype by Alphonse-Eugène Hubert from the Daguerre studio.

And, yes, the Hubert is definitely on my list–a great thing, as close to a piece of the true cross as we're likely ever to get. It's a beautifully preserved whole-plate daguerreotype by Daguerre's assistant, a still life of artistic bric-a-brac, made soon after the process was made public in 1839. Our director and trustees were fearless in going after it at auction in Paris a few years ago, recognizing what a rare opportunity it was.

And the Laurie Simmons is a good guess also, one of a number of contemporary acquisitions that checked off items on the desiderata list that I came with at the start of my Houston tenure–works by Simmons, Sarah Charlesworth, Marilyn Minter, Thomas Struth, Vera Lutter, Richard Learoyd and others. And at the risk of exceeding your instruction to name three or four acquisitions, I have to cite some important group acquisitions: the Plonsker Collection of contemporary Cuban photography; a collection of contemporary Chinese photographs from Larry Warsh and Art Issue Editions; and important groups of work by Dawoud Bey and Sally Mann. And, of course, lots of other 19th-century photographs! But I'll stop.

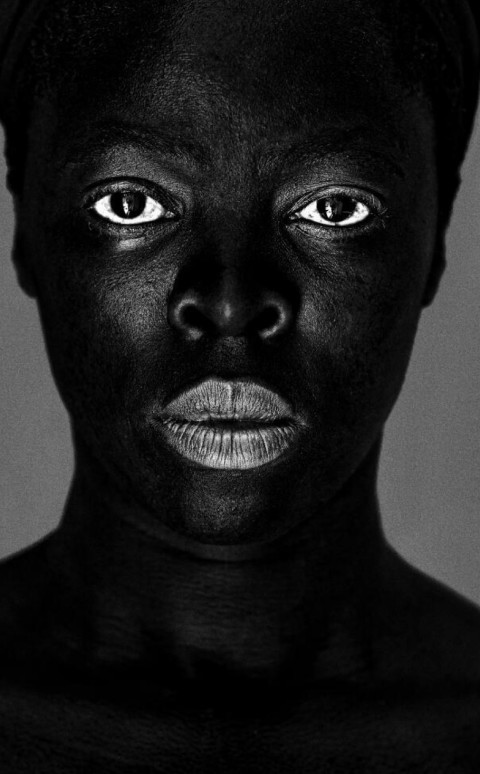

Zanele Muholi, Misiwe IV, Bijlmer, Amsterdam, 2017, photographic mural.

OK, my turn to guess. If I think back on the important acquisitions you've brought into the collection, I'm struck by the way each of them has not only added individual works to the collection, but also expanded the way photography is represented here, so here's my guess: the Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey Collection of vernacular snapshots, fotoesculturas, photo jewelry and other parts of what Daile Kaplan once dubbed "pop-photographica"; Zanele Muholi's self-portrait "wallpaper"; Bruce Conner's Prints box; and Trevor Paglen's time-based media work, Image Operations. Op. 10. Talk about those and why they were important to acquire. And then tell me what I've forgotten that's on your list of proud acquisitions.

LV: That's a pretty good list! Yes, the Levine-Ramey Collection was really special. It allows us to explore how photography touches everyone's life, on a daily basis. And also that influence isn't a one-way street, flowing from "high art" to "everyday." It's two lanes. A mix of influences! The Zanele Muholi mural makes me laugh because I remember a certain curator had a bit of an issue buying a file for a re-printable mural (cough, cough, Malcolm). But it's an amazing work–an intense close-up self-portrait stretching from floor to ceiling–with an amazing message about belonging. It's an audience favorite every time we install it, and it broadens our understanding of what photography can be in this time. Bruce Conner's Prints box was a fun one! Honestly, it was a surprise that I was allowed to acquire a box of Xeroxes for the museum. But it's such a great conceptual work. After being fingerprinted for a teaching position, Conner argued with San Jose State University for over a decade for the return of his fingerprints claiming they were art, and documenting every interaction and collecting it in the box. Still relevant today when we think about issues of identity!

Paglen's Image Operations. Op. 10 is always a favorite of mine, for much the same reason. It always asks us to think about what we know, and to expand what we think. That work overlays three types of computer vision (AI) on a video of musicians performing three movements of Debussy's String Quartet in G Minor. It's visually gorgeous, sonically divine, and incredibly thought-provoking. What's better than that? It's also part of a broader effort to expand our time-based media ("video art") collection. Photographers have been making film and video works for more than a century, and it's important that our collection reflects that overlap, especially as this interchange of media is increasing exponentially with contemporary artists. We've even dedicated one of our galleries for the display of time-based work.

MD: What else did I miss that should be on your list? Since I rattled off a lot more than three or four, you get to add a few, too.

LV: I'll just add our James Luna, Half Indian/Half Mexican. It's a five foot by 12 foot triptych showing the artist in profile with stereotypically Indigenous hair and accessories, stereotypically Mexican hair and facial hair, and facing forward with both sides evident. It poses critical questions about personal identity and what photography has taught us to expect of people and cultures. It's an absolute showstopper in the gallery.

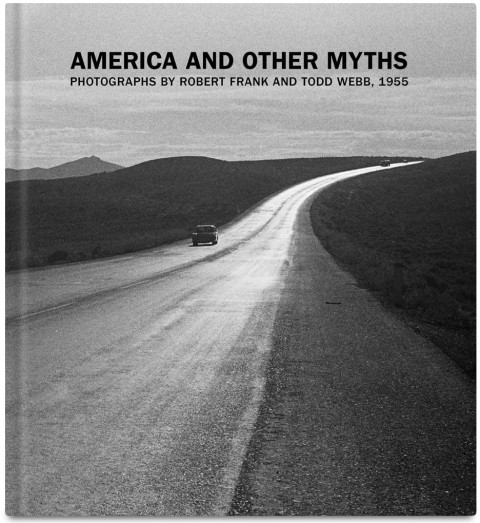

MD: Not that I've been goofing off for the past dozen years, but I'm still in awe that you've been able to crank out a series of groundbreaking exhibitions and catalogues one after another: Georgia O'Keeffe, Photographer (in 2021), Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power (in 2022), and America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955 (in 2023). Share how those came about and what's in line next.

LV: You absolutely share in the credit for each of those projects. Our teamwork allowed me to be able to balance the workload, and your faith in me and my abilities gave me the push to produce. So thank you! As for how they came about...it was serendipity! Georgia O'Keeffe Museum director Cody Hartley mentioned the unattributed photos in the collection to me, and that set me off on that first project. I've always been a massive fan of Gordon Parks, and the Foundation, under the amazing direction of Peter Kunhardt, Jr., offered the Carmichael project during a visit, and I jumped at it! Parks's profile of Carmichael that was published in LIFE included only a handful of photographs, but Parks shadowed Carmichael for months. It was a great opportunity to re-construct Parks's original vision. And then Todd Webb and Robert Frank came about because MFAH has a close, family history with Robert Frank, and I was offered the Webb work by Betsy Evans Hunt, the director of his archive. I was doing research for the O'Keeffe project, because Webb was the one who taught O'Keeffe to photograph, NOT Steglitz. Betsy revealed that Webb and Frank both got Guggenheims for cross-country projects in 1955. It was great putting their visions side-by-side for the first time.

One thing leads to another! In fact, my next project is inspired by Gordon Parks. I've been researching the broad array of picture magazines made for the African American community from 1930 to 1970 to find out who the photographers were, and what kind of images they were producing in these critical decades for a Black middle class. Parks worked for LIFE, of course, but also for FLASH in the 1940s, Circuit's Smart Woman, and Essence magazine. So far, I've uncovered more than 350 magazines, and 900 photographers, most of which we've never heard of! It's going to be an eye-opening exhibition. It will open in Houston in March 2027.

MD: The Black magazines project is so impressive. You've done so much original research that will form the basis not only for this exhibition but also for future projects by other people. My goals for the next 15 or 20 years are a bit more modest than yours! Reading for fun, learning Spanish, trying ceramics, testing new recipes, travel, walking the dog, taking afternoon naps. But I also plan to keep an informal affiliation with the MFAH, keeping an eye on auctions and dealer inventories, especially for 19th-century material–those "little brown photographs" that you all make fun of me for loving. Between the riches of the Manfred Heiting Collection and the works I was able to bring in over the past dozen years, Houston now has an absolutely top-tier collection of 19th-century photography, and I want to help ensure that it keeps growing when great works come on the market. Since Anne Tucker had already built a collection with exceptional strength in the 20th century, my goal when I came to Houston was to build "the bookends"--a more expansive and deeper representation of the 19th century, particularly in areas that had been of secondary interest to Manfred (daguerreotypes, for instance), and photographic work by contemporary artists that had been out of reach for Anne. I feel pretty good about all that, but there are still things on my desiderata list that remain to be checked off.

Always trying to proselytize for the 19th century, I also tried to introduce early photography to our supporters and public, integrating it into our departmental installations, our Photo Forum events, and our acquisitions program. Since most of your exhibitions and acquisitions in Houston have been 20th- or 21st-century, I think people might find it surprising to learn that your Ph.D. dissertation was on a 19th-century American subject. What did you write about, and do you still have an interest in the production and reception of photography in 19th-century America?

LV: Absolutely! I might tease you about those little brown photos, but I have an interest there as well. My dissertation examined American photography at World's Fairs, and how America was defining itself as a young nation through photography. My interest in the 19th century is cultural. What does the proliferation of studio portraits say about social trends? I still harbor a deep obsession with Napoleon Sarony, not only for his outrageous self-presentation, but also for his court case establishing photographic copyright in the US. But as you know, for me the pleasure of the 19th century is always in connecting it to the present day, to show that nothing is a straight line in photography, we're always looping back and around. It was fun to collect the infamous Monkey Selfie for the museum and make that connection to Sarony. That Monkey Selfie might be the most popular photo we have! People love the story. David Slater encouraged a black macaque to photograph itself, but then found himself embroiled in a series of lawsuits, including one that fought for copyright for the monkey! Eventually, a judge dismissed the claim, and Slater owns copyright, but it's all part of the same circle.

It's interesting to think about how both the photography market and the field in general have changed, even in the years I've been a part of it, but I'd love to hear your thoughts about that, especially with regard to 19th-century works. You have a longer perspective on that than I do.

MD: A polite way of saying how much older I am! No, it's true that a lot has changed, though the story really begins in the mid-1970s, before I was a part of it, with collectors like Pierre Apraxine for Gilman Paper Company, Richard Pare for Canadian Centre for Architecture, Sam Wagstaff, Paul Walter, and a few others, guided also by some important dealers and auction experts–André Jammes, Hugues Autexier and François Braunschweig (Texbraun), and Gérard Lévy and Francois Lepage, all in Paris, Howard Ricketts and Philippe Garner in London, Sean Thackrey in California, and others.

It's only in the 1970s that regular photo auctions began, and until then, there were only a few photography galleries, few collections on which to train one's eye, few scholarly books on the history of photography, and virtually no academic programs focused on photo-history (the appointment of Peter Bunnell at Princeton in 1972 was the first endowed professorship in the history of photography).

There was a rush of material to the auction houses in the decade that followed. By the time I came along in the late-1980s, the 19th-century photography market was well established (though everything seems so cheap when I look at the old auction catalogues now!) and the models for scholarship in our field were in place. That said, there was–there still is–plenty of primary research to be done about early photography and photographers, and it was still possible–more than it is today–to build a strong collection of photographs from the first quarter century of the medium. I think that the general market for 19th-century photographs is significantly weaker today than 20 years ago, but as is the case in many areas of art, there can still be fierce competition for works of the highest quality.

Lisa, you're more in touch with both the scholarship and the market for contemporary photography than I am, so I'm curious what changes you've seen during your time as a curator.

LV: Well, one of the many things I'm grateful for at MFAH is our shepherding of the Joan and Stanford Alexander Award. That annual award provides small grants each year to two doctoral candidates working on dissertations that concentrate on photography. So once a year, we get to hear exactly what new scholars are thinking about, what work they are concentrating on. It allows me to see how the field is shifting! One of the things that's evident is that New York is no longer the center of the art world. So many artists are living in different places around the country, and scholars are investigating groups from coast to coast and around the world. Also, still life is back in a big way. So many contemporary photographers have chosen to rethink this genre and to drag it out of its typical bougie European character. The market...well that's a different story. Ask me again next year and I might have a better handle on the craziness that's going on.

MD: Finally, just between us, as you begin leading the MFAH Photography Department, what scares you the most, what excites you the most, and what are your big goals for the decade ahead?

LV: Well, as you taught me, I'm trying not to dwell on the scary parts. But I think living up to the legacy that you and Anne set is intimidating to say the least. As for my goals, they might be a little obvious. I want to continue to build on the incredible collection here at MFAH, especially by deepening the geographic scope of the collection, and embracing time-based media. I want to continue the legacy of producing ground-breaking exhibitions while keeping visitors engaged with our permanent collection galleries. And I'm focused in the short term on our study center. The Anne Wilkes Tucker Photography Study Center is, I think, the most beautiful study center in the country. I'm working on making it the most active one too. I want classes, groups, researchers, artists, and just interested viewers to come to the Study Center to have up-close, life-changing experiences with the amazing objects at MFAH. I am a curator because I had access to a study center in my college years. Those visits truly changed the course of my life. I want that for others.

Michael Diemar is editor-in-chief of The Classic, a print and digital magazine about classic photography. In August 2025, he cofounded Vintage Photo Fairs Europe, an organization focused on promoting independent tabletop fairs in Europe and spreading knowledge about classic photography in general. He is a long-time writer about the photography scene, writing extensively for several Scandinavian photography publications, as well as for the E-Photo Newsletter and I Photo Central.

Share This